To Lean or not to Lean?

The Lean business methodology works for every business – except for those it doesn’t.

The model is increasingly popular in business schools and incubators throughout the region and provides an alternative to the traditional route of developing a business plan in order to run a company.

However, although it works well for some kinds of companies, applying the model in full can be less useful for others and must be applied “to the best scope possible”, says Ozan Sonmez, the startup accelerator lead for King Abdullah University for Science and Technology (KAUST).

Startups with expensive prototypes or a potentially tricky customer base, but which still want to apply the Lean model must adapt it slightly to fit their circumstances.

What is it?

The Lean concept, launched in 2011 by author Eric Ries, popularised the terms ‘minimum viable product’ (MVP) and ‘pivot’.

The basic premise is that instead of writing a business plan before consulting customers or investigating how it’ll work, entrepreneurs should do the R&D as they go, right from the start.

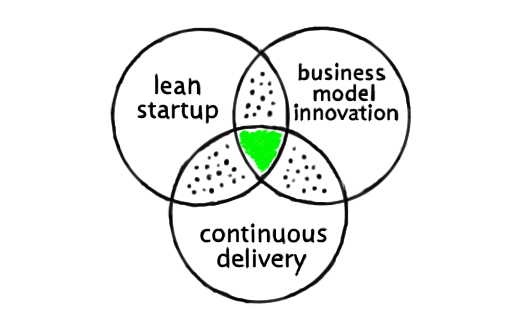

The model has three pillars:

- accept from day one the idea is a hypothesis – before embarking on months of research – and create a ‘business model canvass’ describing the assumptions around the idea.

- test the idea on expected customers or partners, such as manufacturers, covering every aspect of the business. Those questions, on everything from customer acquisition strategies to pricing, will help you develop a basic version of the idea to take back to those same people for more feedback.

- and finally, the model calls for ‘agile’ development. Instead of spending considerable time on building a product without any or much input from your potential customer, the agile method quickly builds a prototype through iterating (small changes to the previous design) or pivoting (large shifts away from ideas that don’t work).

It means startups don’t spend their precious cash reserves on building a fully-designed and tested final product, be it software or hardware, which may not be precisely what customers want or which needs to be altered to fit the demands of a changing marketplace.

The model isn’t without its critics: Paypal cofounder Peter Thiel is a vocal opponent, saying all it means is “listening to what customers say they want”, rather than what they might need in the future, and that it’s a “code for the unplanned”.

“Would-be entrepreneurs are told that nothing can be known in advance: we’re supposed to listen to what customers say they want, make nothing more than a ‘minimum viable product,’ and iterate our way to success. But leanness is a methodology, not a goal. Iteration without a bold plan won’t take you from zero to one,” Thiel wrote in his book Zero to One.

Others, such as marketer Dan Kaplan, say the model is the very essence of planning, allowing entrepreneurs to know that a product will appeal to customers before they start selling it, rather than guessing.

Who’s it useful for?

The Qatar Business Incubation Center’s (QBIC) head of incubation, Ahmed Abdulwahab (below), said Lean methodology could be applied to any sector, bar biotech because repeated iterations of a drug or life-saving equipment wasn’t an option in life-or-death situations.

head of incubation, Ahmed Abdulwahab.

He said early testing proved whether an entrepreneur’s idea was “a nice to have or a need to have”.

“If it’s just a nice to have, another social media platform… or another phone design, or another kind of product that’s not really special, then you don’t really want to waste time on it,” he told Wamda.

Furthermore, he held no truck with entrepreneurs who refused to reveal their idea before having a viable product to sell.

“When an entrepreneur comes to us and says I have a great idea but I can’t talk to anybody, we usually say keep it to yourself for 20 or 30 years and you live with it.”

He said there were currently 37 startups at QBIC, all of which were included in its Lean Startup program, and they ranged from a perfume developer to the maker of a t-shirt that absorbs heat.

KAUST too teaches all of its startups the Lean model, aiming to get as many customer appvoals in the first six to eight weeks of incubation.

“We want our startups to sell to get some revenue, for the crappiest product, because they always want to make it perfect…but the customer doesn’t care,” Sonmez said. “If they get to customers faster, they will get investment faster.”

Who’s it not useful for?

Sonmez, however, said there were instances where the Lean model was ill-suited to developing a product. Abdulwahab agreed that it was easier to apply to software-related products than hardware, though all the latter required was more customer research before building.

KAUST draws its startups from within the university. This means the kind of products being commercialized, ideas such as cleantech membranes or heavy engineering equipment, where a single prototype may cost up to $1 million.

Governments, which tend to be major economic players in MENA, can also be the target customer when it comes to, for example, health or energy-related products. Sonmez said governments, unused to dealing with startups anyway, wanted a ready-made solution.

And unlike with a B2C product where a startup could go to Indiegogo and raise money for a prototype but also to gauge interest, it was harder to find real problems or get to a paid-for beta version quickly when dealing with corporations and a B2B product.

But he added that although, for example, a miner may not invest $1 million in a single new piece of equipment that would solve all of their problems, they may invest in a smaller version or machine that would solve part of a problem.

KAUST tries to help startup working with “deep tech” to find lean ways of running the business, such as in finding customers.

Sonmez said local entrepreneurs are lucky because while elite universities in the US are still teaching business plans and traditional methods of starting a company, many Middle East incubators are leapfrogging over the old ways and adopting the new.