Changing the way MENA moves

Smart transportation has the potential to change many things in modern life, from the very roads people use to get to work to the way whole cities are planned.

In the Middle East the possibilities are mind boggling.

How much wealthier would Egypt be if Cairo’s traffic problems weren’t a 4 percent of GDP drain on the economy? Would a quarter of Lebanon’s population still live in Greater Beirut if better transportation systems meant they didn’t have to? And, on a darker note, what would those 7,898 Saudis who died in road accidents in 2013 be doing today?

Throughout the region there is evidence that smart transportation - vehicles and infrastructure whose purpose has been super-charged by the internet - is a concept whose time has come. As Ismail Zohdy told Wamda, the technology is here, it’s the application that is lacking.

He says the top three problems smart transport will solve are safety, mobility (as more people are able to travel with fewer delays), and environmental.

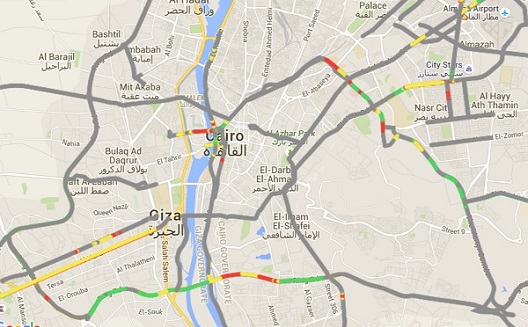

The problems caused by failing or inefficient transport system are wide reaching. (Images via Rachel Williamson)

Mobility

Getting growing populations from A to B without overloading existing infrastructure, such as is happening to Cairo’s excellent metro system, or adding to current jams, is an issue being taken up by governments, corporations and startups throughout MENA.

In terms of carpooling, bus-pooling, car sharing and shared bicycles there are local versions of global giants available from Dubai to Morocco.

A 2011 study from the University of California found that every car sharing vehicle removed 9-13 others from the road. While no such study has been made for MENA countries, this is unlikely to be the case here.

Owning a car is still a status symbol for upwardly mobile Arabs and North Africans. Global consultant IHS Automotive estimated in 2014 that light vehicle sales in the GCC alone would double that of both Western Europe and the US by 2022, touching 1.74 million sales in that year.

To put that in perspective, the GCC’s population today is just over 50 million. Compare that to Egypt where it’s, unofficially, just over 90 million and one of the 14 largest car markets in the world, according to insurer Swiss Re, yet only about 12 percent of Egyptians own a car.

As a result, in Egypt’s case at least, smarter transport than even that available today is essential. Egypt’s most famous urban planner David Sims said in 2014 that if the government took no action, by 2025 road corridors leading into the city would be paralysed and Cairo’s satellite suburbs would be in inaccessible.

It's easy to forget that congestion is an economic burden - until you try to schedule more than two business meetings in a day in Cairo.

But ride-hailing and carpooling are just the beginning, says Zohdy, and must come alongside policy decisions. He envisions a future where trucks are prevented from certain roads at certain times of day, while traffic management apps like Bey2ollak incentivize drivers to travel at off-peak hours by suggesting a route via their favorite cafe - and offering a windowed discount on their favorite food or beverage.

Safety

The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimated that in 2015 road accidents cost all countries on average 1-3 percent of gross national product. This cost is from treating victims, reduced productivity of family members who may need to care for victims, repairing vehicles, road maintenance, and investigating incidents.

Interestingly, expensive advanced technologies to reduce road accidents are likely to also disproportionately benefit the poor.

“Traffic accidents disproportionately affect the poor as pedestrians, cyclists and motorcyclists are the most vulnerable road users and account for the majority of traffic-related deaths and injuries,” according to a 2012 World Bank report on urban transport in Morocco. The remark is relevant throughout the region, be it for those who rely on Lebanon’s unroad-worthy private microbuses to Egypt’s accident-prone inter-city public transporters.

Advanced car technologies such as semi-automatic braking and reversing cameras and radars are already available in the region, but vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) technology is not here yet (think ‘platooning’, where autonomous vehicles communicate wirelessly and follow each other closely), and the practical application of vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I) is currently aimed more at creating smart parking spots in Dubai.

Right now the safety angle is being covered by apps and Internet of Things (IOT) devices (click here for an IOT guide), and in practical terms this means targeting insurance premiums for good drivers and monitoring commercial driver behavior.

UAE startup Dashroad is one that’s marketing itself in both areas. It provides a ‘black box’ that connects to its app and monitors driver behavior and vehicle performance. Founder Faheem Gill told Wamda in March that he was pitching the device as a fleet management system (they’ve already done a deal with Careem) and as a way to lower individuals’ insurance premiums by making it possible for companies to offer lower payments in exchange for good driving.

Another angle is in after-crash services. Secure Drive Company from Tunisia uses an embedded device in cars that automatically alerts emergency services and designated family members following an accident.

These startups are two of the handful of MENA hardware/software startups to launch in what is an extremely prospective market. In 2013 consultant Booz & Company (now Strategy&) suggested that by 2020 the global safety technology segment would reach $41 billion.

In March, a whitepaper from Swiss Re and location technology company Here, estimated that by 2020 just over $20 billion could “be trimmed from annual premiums as a result of increased road safety enabled by automated car technology”, or telematics.

It’s a term that refers to any device that merges telecommunications with information processing. Connectivity comes from embedded devices, such as the above, and tethered through a smartphone; the former, like Texas-based Vinli’s USB, allow cars to send vehicle data to the cloud.

“In the long-term, cars will link to the Internet of Things (IoT), communicating with other vehicles and to the surrounding infrastructure,” the Here report said. “We expect that by 2020, more than two-thirds of cars sold worldwide will have some form of connectivity.”

Environmental

The obvious environmental impact of smarter transportation systems and vehicles is efficiency: more people using fewer vehicles, that are maintained to a higher standard and more often.

Startups such as Beliaa, Salla7ny and Mosa3ed (all from Egypt) help with managing car maintenance, while others - Carpool Arabia in the UAE, Carpolo in Lebanon and Kartag in Egypt - allow people to share their vehicular resources.

Interestingly, however, they might even be having an impact on the very way cities are built.

Careem founder Magnus Olsson told Wamda that while it was a bit early to consult on urban planning, they are advising governments on traffic patterns, using their in-house data. He said mapping and urban planning companies were also approaching the firm to access their data.

Uber’s regional manager Jambu Palaniappan said that as more satellite suburbs were built around cities like Cairo there were more opportunities to figure in smart transport options. He told Wamda they were working with authorities to improve traffic flows and assess where public transport options could be a better option.

With the sheer amount of data being created from the existing transport apps and devices, the door is open for other opportunities, like mapping companies or big data crunchers, to help create other applications that use the data to assess driver behavior. While MENA has wholeheartedly jumped aboard the smart transport train, there is plenty of room yet for further innovation.