Fintechs face reckoning as easy money dries up

By Imani Moise, Siddharth Venkataramakrishnan and Joshua Oliver

As a wave of fintechs rode successive funding rounds to ever-higher valuations over the past five years, Swedish buy now, pay later company Klarna declared its ambition to become the Ryanair, Tesla and Amazon of the sector.

But now as central banks raise rates in a fight against surging inflation, Klarna is trying to raise fresh cash at less than half its peak $46 billion valuation and fintechs are having to come to terms with a world where expansion can no longer be fuelled by cheap money and business models must be demonstrated by profits.

A record amount of investment poured into fintech companies in 2021, but many now struggle to raise fresh funds and are discussing selling themselves or accepting lower valuations to stay afloat, according to investors, analysts and executives in the industry.

On Thursday, payments services provider SumUp raised cash at a valuation of €8 billion — significantly below the €20 billion valuation mooted earlier this year.

And as belts tighten, a fintech’s chances of survival may be measured by the amount of cash sitting on its balance sheet. “You are in panic mode if your runway is less than a year,” said Erik Podzuweit, founder and co-chief executive officer of German investment app Scalable Capital.

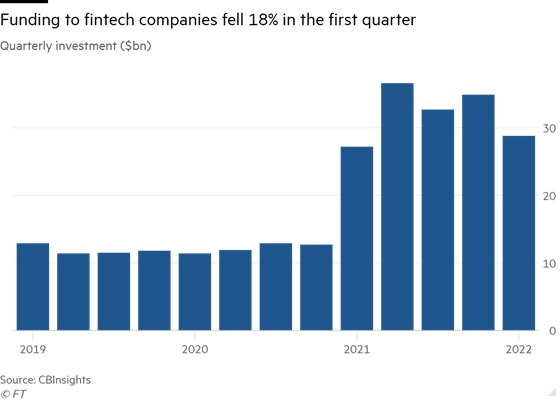

Venture capital firms more than doubled their investments in the sector last year to $134 billion, helping fintech valuations outperform any other tech subsector, according to Crunchbase data. Funding peaked in the second quarter of 2021 as investors such as Accel, Sequoia Capital, SoftBank and Berkshire Hathaway backed groups including Brazilian digital lender Nubank, German broker Trade Republic and Amsterdam-based payments company Mollie. Financial services companies accounted for roughly $1 out of every $5 in venture capital investment last year.

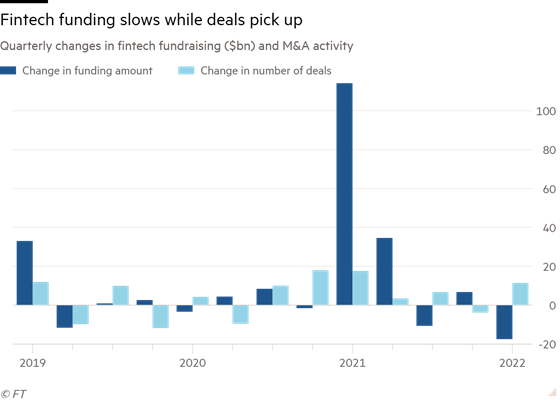

But now public fintech valuations have collapsed even faster than they climbed as funding slowed sharply in the first quarter. Fintech valuations have had a steeper decline than any other technology sector, according to a recent report by Andreessen Horowitz partners, which cited data from Capital IQ. Valuations fell from 25 times forward revenue in October of 2021 to four times in May.

Fintech fundraising in the most recent quarter dropped 21 per cent to $28.8 billion from the record high of $36.6 billion reached in the second quarter of last year, according to CB Insights.

“It was easy for funds that raised a tonne of money to say, ‘oh, we’re just going to double the valuation’ . . . it doesn’t necessarily follow company performance,” said Jonathan Keidan, managing partner of Torch Capital, which has invested in fintechs such as Acorns and Compass. “The effects will be public by the fall.”

Many fintech companies raised capital at lofty valuations based on ambitious growth targets, said Arjun Kapur, managing partner at Forecast Labs. “With all the market changes, most of them are not going to hit the goals they signed up for, which means the business is not worth what it raised.”

Though he expects the sector will bounce back over the long term, “many businesses will get squeezed out in the process”.

Investors have grown particularly sceptical of consumer-facing digital challenger banks as high inflation lowers how much people can save and increases the likelihood of defaults. Funding to banking fintechs plunged 48 per cent to $4.4 billion in the first quarter compared with the same period last year, according to CB Insights.

Robert Le, fintech analyst at PitchBook, said that a bifurcation in funding was likely, as consumer-facing fintechs struggle while those selling software to other businesses will prove more stable. Among those is UK cloud banking fintech Thought Machine, which doubled its valuation to $2.7 billion in its latest funding round in May.

Meanwhile, executives such as Yorick Naeff, chief executive of Dutch broker Bux, are considering postponing planned fundraising rounds. “These companies, including us, should focus more on the path to profitability,” he told the Financial Times. “If you are organised in a way that is just focused on growth . . . you are going to run into trouble.”

Many consumer fintech companies in the US had started to dial back their marketing budgets in an attempt to conserve cash, said David Sosna, chief executive of Personetics, which provides marketing insights for the banking industry. “We definitely see some [clients] saying, ‘OK, maybe we need to stop or slow down.’”

Bankers are advising companies to conserve as much cash as possible to ride out what will probably be a difficult two years for fundraising.

“When you factor in the time it takes to raise a round, you probably need 30 to 36 months runway so you’re not forced back to the market,” said a senior banker at a US commercial bank. Only extremely strong companies would be able to raise even at the same level as last year, the person added.

Freetrade, the UK broker valued at £650 million in November, raised £30 million through a loan last month. Chief executive Adam Dodds said at the time that the move aimed to shore up the company’s balance sheet without having to revalue it: “It’s choppy markets. To zero in on a valuation at this point is maybe not that helpful.”

In addition to a lower valuation, which can be an embarrassing signal to markets and hurt morale internally, down rounds may carry stricter terms such as strengthened liquidation protocols and anti-dilution protection, said S&P Global Market Intelligence analyst Tom Mason.

Selling out entirely was becoming an increasingly attractive option for many companies, said Keidan at Torch Capital. Apple’s privacy changes have significantly increased customer acquisition costs, making existing customer bases more valuable at the same time fintech valuations are coming down. Boards began exploring potential sales in the spring, he said.

Fintech acquisitions — already on track to pass 2021’s record — will probably accelerate through the rest of the year as traditional financial companies such as JPMorgan Chase and Mastercard take advantage of relatively cheap software groups.

“I’m seeing it brewing very fast right now,” said Michael Abbott, global banking lead at Accenture, adding that tie-ups between fintech challengers and incumbents are on the rise.

Deals so far this year include UBS’s acquisition of Wealthfront and Fiserv’s purchase of Finxact.

“What consumers want is the best of what the neobanks have to offer in terms of experience and an ability to get products quickly, but at the same time what they’re going to need in a rising rate environment is the balance sheet of a bank,” said Abbott.

One investor at a large private equity firm said they had received a steady drumbeat of pitches from fintechs looking to sell themselves in recent weeks but had passed on all of them.

“Who’s to say this price is really the right price? What if six months from now that price is actually considered too expensive?”

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2022

© 2022 The Financial Times Ltd. All rights reserved. Please do not copy and paste FT articles and redistribute by email or post to the web.