Dark stores will create more collaborators than competitors

In the absence of physical shopping during last year’s lockdowns, demand for e-commerce soared, most notably in the grocery segment. As consumers realised the convenience of buying their fruits and vegetables online, several new e-grocery startups came to market. Other platforms introduced their own e-grocery offering including many food delivery platforms like Talabat and Deliveroo, e-commerce marketplaces like Noon, and even cloud kitchen operator Kitopi.

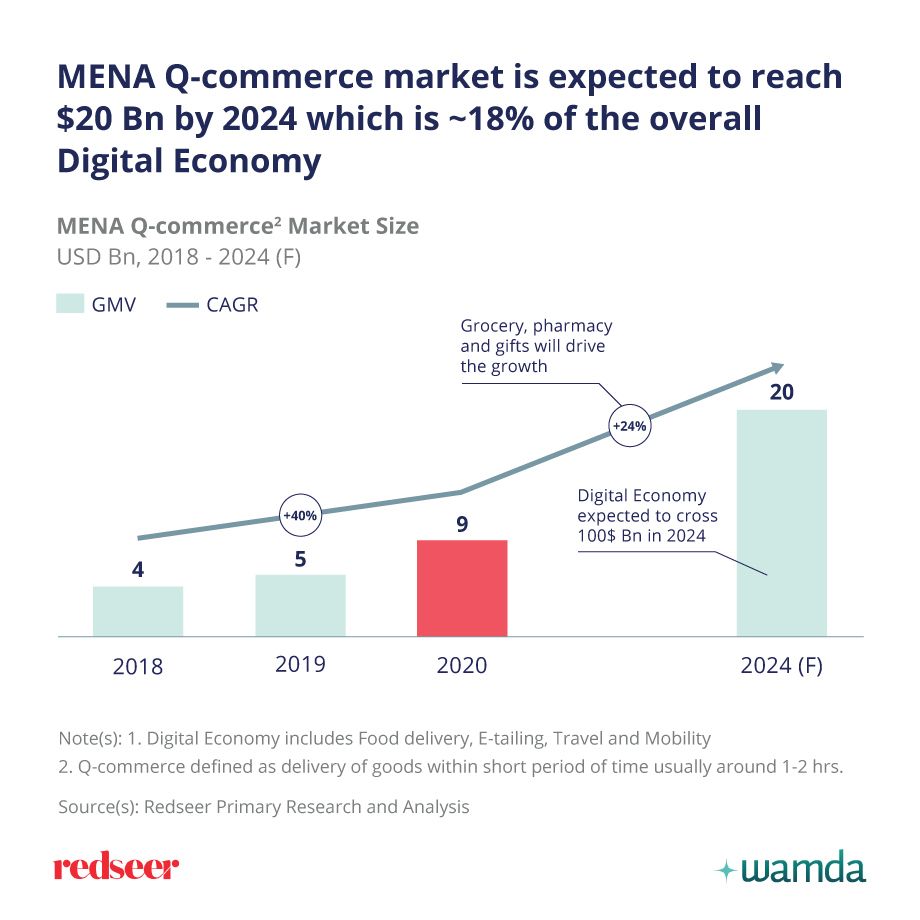

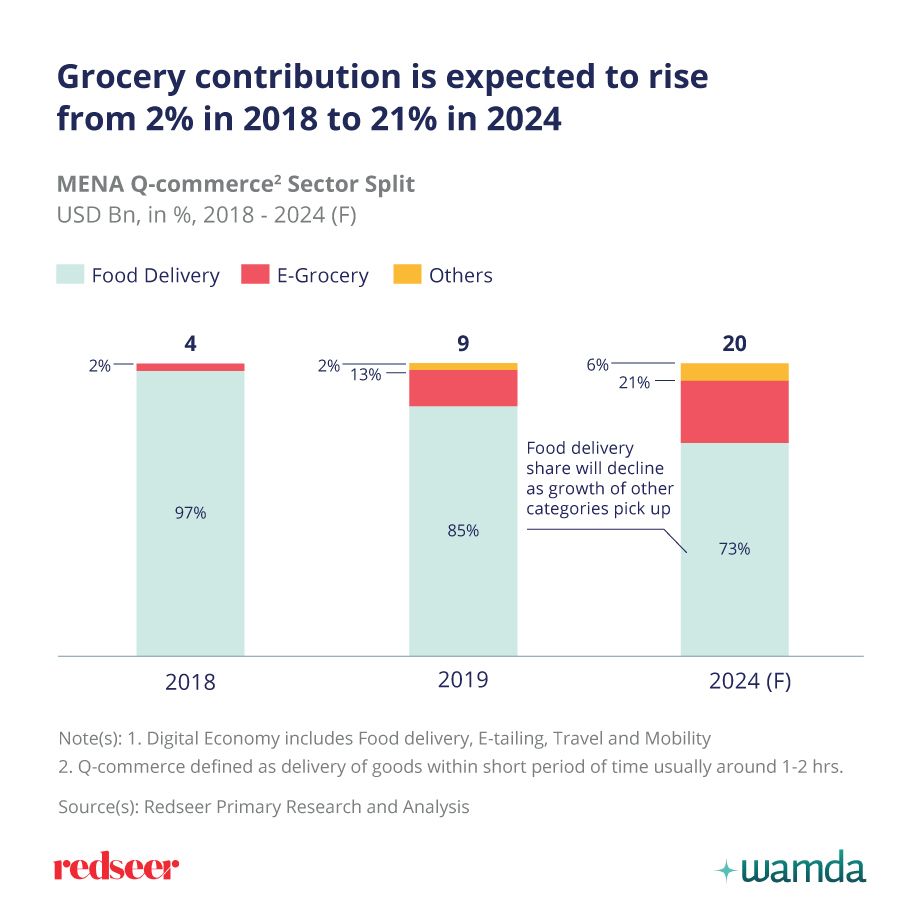

With this influx of competition and consumer choice, quick commerce, that is delivery in under an hour (or two), began to emerge. Research from UAE-based consultancy firm RedSeer, predicts that overall q-commerce (of all segments including food delivery) in the Middle East and North Africa (Mena) will reach a value of $20 billion by 2024, driven primarily by the rise of e-grocery, which is set to be worth close to $21 billion by then.

At the crux of such rapid delivery is an infrastructure of “dark stores”, which are delivery only warehouses, typically housing the most popular foodstuffs, set up close to built up areas.

“The dark store really helps to provide fast delivery and speed above all, and it also gives control over the whole customer experience. These dark stores will be the infrastructure for all e-commerce players in the future,” says Sami Alhelwah, co-founder and CEO of Saudi Arabia-based e-grocery Nana. “It will be a core element in any e-commerce business who wants to have access to customers… and a core element in logistics because they’re considered like dispatching areas or fulfillment centres for the neighbourhood they are in.”

Nana currently covers 14 cities in Saudi Arabia where it acts “as a technology company and a logistics company at the same time” with plans to become “the AWS [Amazon Web Services] for grocery”. It recently launched 30 dark stores in Riyadh, with another 20 in the pipeline.

Of course, short delivery times are nothing new for the food sector and cloud kitchens are arguably the dark stores of food delivery platforms. But whether it is food delivery or q-commerce in e-grocery, they all rely on proximity to the end consumer and a large enough logistics fleet.

“Not every single player needs dark stores. The infrastructure is costly, but at the end, once you build this infrastructure, it becomes cost-effective,” says Alhelwah.

Traditionally, consumers across Mena buy grocery items from local convenience stores, also known as the baqala, whose value is mainly speed but whose disorganised, generally autonomous, presence leaves it with “a lot of problems in supply and overall customer experience,” explains Alhelwa.

But until dark stores completely replace these convenience stores, improving the baqala experience currently depends on utilising more partnerships with existing retailers and convenience stores.

“Coexistence is more the model I see happening, in the medium term, than I think having one or the other,” says Sandeep Ganediwalla, managing partner at RedSeer. “We are speaking about less than 1 to 5 per cent of the market being captured by dark stores, while the majority remains online or hyperlocal or offline. So, replacement is too far away to even think about right now - maybe 15 or 20 years down the line. Right now there's a lot more collaborations that need to happen.”

Newer e-grocery startups are thinking of these collaborations as they shape their final product, and for UAE-based e-grocery startup Yeepeey, the answer is a cooperative “70:30 delivery model” according to founder Monish Chandiramani, where the majority of orders are delivered by merchants themselves. This reduces the costs of inventory, rental, and required delivery workers which generally inhibit the estimated overall profitability of dark stores.

But as a price-sensitive sector, margins on grocery are already low and adding the cost of rapid delivery will only further exacerbate the issue.

“What concerns me is the overall profitability of this sector. The region is now seeing a lot of funding and that's a good thing,” says Ganediwalla. “But not being able to get the economics right and going too aggressive on a single model, and burning a lot of money would be difficult for the sector.

“We’re only at the starting phase of dark stores, more stores will emerge, players like Lulu will participate, grocery will remain the primary sector but we’ll see pharmacy, flowers, gifts as well,” he adds.