Entrepreneurship isn't free - here's why

This article has been cross-posted with Quartz.

There is good news and bad news about entrepreneurship. The good news is that there is emerging global consensus that fostering entrepreneurship should be an integral part of every region’s economic policy. Entrepreneurship is a way to generate growth, with the associated outcomes of dignified employment creation, wealth generation, taxes and fiscal health, and in some cases, innovation and philanthropy. Numerous examples are abound.

But there is “bad news” as well. As I have written, policy surrounding entrepreneurship is extremely complex and confusion is rampant, in part because entrepreneurship is constantly conflated with self-employment, small business, micro-enterprise, innovation, startups and so on. Because of this, policy makers are confronted with a bewildering array of potential solutions—incubators, angel investment tax credits, small business loan guarantees, clusters, accelerators, micro-finance—that seem to work in some situations, yet fail miserably in others. Often, the costs of these programs dramatically outweigh the benefits of entrepreneurship. I wrote Worthless Impossible and Stupid: How Contrarian Entrepreneurs Create and Capture Extraordinary Value partly to shed light on what entrepreneurship is and is not, in part to help dissipate some of the entrepreneurship policy fog so that the benefit-cost ration will be high, and greater than one.

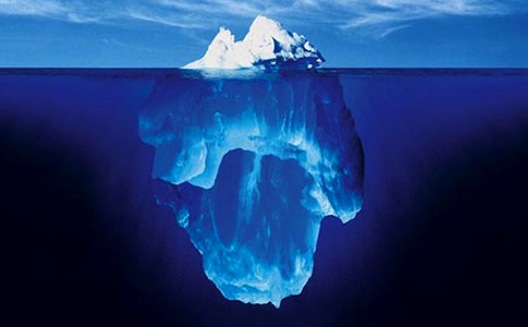

Underlying the policy confusion is an implicit assumption that “the more entrepreneurship, the better” but that can only be true if entrepreneurship entails no social cost. Part of the bad news is that at a societal level, entrepreneurship is not “free”; there is a cost to the contrarian creation and capture of extraordinary value.

Income inequality. It is easy to show that in the short run, successful entrepreneurship creates income inequality in a specific region. Just imagine the impact of 1,000 multi-millionaires or billionaires from the Facebook IPO: increased housing prices, costs of some services, potential flight of children to private schools and so on (good things happen too). I think in very open societies this works itself out in the longer run so that a much broader base benefits, but in many less open societies it can contribute to chronic social stratification.

Social friction. The Singaporean government is disappointed at the strength of entrepreneurship in the country despite the great prosperity and innovation. One of the key reasons entrepreneurship in Singapore suffers is that the government and the culture discourage non-conformity and independent thinking.

Challenge to authority. Closely related to nonconformity is challenge to authority and to autocratic systems. I have often said that the “role” of the entrepreneur is to look across the courtyard and determine the most effective path. That frequently means cutting across the lawn, despite the fact that some central authority has determined where the sidewalks should be. Entrepreneurs need to obey the law, but they generate value by challenging convention and questioning authorities’ often arbitrary or self-serving dictates.

Social mobility, up and down. Aspiring entrepreneurs in numerous countries believe that the deck is stacked against them because of their age or gender, their status, their race or ethnic background, or just because they were not born with the with the right connections. The doors of entrepreneurial opportunity are jammed shut for many. But for entrepreneurship to flourish, mobility has to be based on merit, not birth. The flip side of a move to meritocracy is that those who previously succeeded through family connections or royal entitlement will have to be susceptible to market forces and risk possible failure.

I have written and spoken extensively about the social and economic benefits of the contrarian creation and capture of extraordinary value, I began to wonder, if entrepreneurship is so good, then why isn’t it easy? There are several causes, but it has become clear to me that one of them is that we mistakenly believe that entrepreneurship is “free,” that it is without social costs. Until we recognize the price, it will be that much more difficult. More generally, one of the several major causes of the disappointment or outright failure of much of entrepreneurship policy and many buzz-heavy related programs is a confused and often naïve conception of entrepreneurship. If society and its leaders sincerely want to reap the benefits—employment, taxes, and wealth—and make sure they exceed the costs, we need to develop a more realistic view of both cost and benefit, both of which are significant when it comes to the creation and capture of extraordinary value.