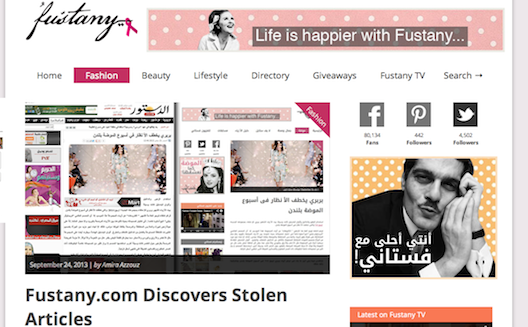

Egyptian entrepreneur Amira Azzouz fights back against content theft

Last week, Amira Azzouz, founder and Editor-in-Chief of Fustany.com, the fashion and lifestyle site for Arab women, was doing some late-night SEO work on the site’s digital archive. Searching for several Fustany headlines turned up articles with the exact same titles on several other regionally popular and well-regarded websites. With a sinking feeling, she clicked on the links, and as the articles loaded her fears were confirmed: Fustany content had been copied, pasted, and published – stolen and plagiarized – by other, bigger websites, with no credit given to Fustany or the people who had written them.

Fustany, Azzouz, and her team are just the latest victims of scraping, the practice of stealing part or all of an article from one content-based website for use on another, with or without any attribution to the original author or publisher. While this certainly happens in well-developed web markets like the United States and Europe, the dearth of intellectual property rights legislation in the Arab world – especially regarding internet-based claims – makes the internet in these markets something of the Wild West, complete with bandits and vigilantes. Without any formal or efficient system of regulation, people have to make and enforce their own rules.

Azzouz’s immediate reaction was along these lines of DIY justice: the next day she penned an acerbic post, explaining exactly what had happened, pointing fingers at the wrongdoers, and posting screenshots that back up her accusations. The sheer volume at which sites were scraping her content, about shoes, fashion shows, and beauty trends, among other topics, is exceptional: Egypt’s Dostor.org, one of the seven top newspapers in Egypt, according to Azzouz, stole 25 articles, and Anaonline.net, also based in Egypt, stole 23 (other offenders include Bokra.net, Elhawanem.com, and Mojtamai.com). In the case of some articles, like "Burberry grabs attention at London Fashion Week", the headlines, images, and text are all copied. She ended the post by announcing that she would be filing a copyright infringement lawsuit against the offending sites as soon as possible.

She realized how serious the situation was when Dostor.org’s Editor-in-Chief called her up later that week. He, inexplicably, was strident rather than apologetic: in a phone call with Wamda, Azzouz recalls his saying “how can you accuse a big newspaper like us of doing this?” When presented with incontrovertible dated screen shots, he changed his tune: “I’ve been in this business a long time and things like this happen. Why are you making a big deal?” He went on to demand she take down the article making the accusations, while refusing to apologize publicly. He did promise to remove the stolen articles, but over a week later, the articles remain up.

Content scraping is indeed a big deal. Writer Tim Conneally, himself a victim, writes of its negative consequences: “the wholesale reproduction of my content hurt my site’s page-rank and drove down the value of my advertisements,” which can also go onto damage a site’s SEO return. This, of course, is in addition to the basic moral and ethical considerations that prevent respectable people from stealing others’ ideas.

To address this problem, entrepreneur and developer Rami Essaid helped created Distil.it, which he told Nibletz “is the first content protection network that helps companies identify and block malicious content scraping and data theft,” mostly performed by bots.

But while Distil and other services might be able to detect automated bots behaving suspiciously on one’s networks, his software does not solve the problem of a human editor personally copying and pasting content from one site to another, which seems to be what happened in the case of Azzouz and Fustany. Until someone creates something better, perhaps the best way to prevent scraping remains simply searching for articles 10, 20, 30 days after they’re published to see if they’ve been stolen, and then taking action along traditional legal avenues.

In the case of Fustany, Azzouz’s plans include filing a complaint with Egypt’s journalist syndicate (nakaba in Arabic), as well as going ahead with the lawsuit she threatened to file in last week’s post. There are examples of these online copyright infringement cases being settled in favor of the little guy (for instance when Lebanese newspaper L’Orient Le Jour used a prize-winning photograph taken by Lebanese photographer Abir Ghattas without permission), but they take years to resolve and offer little remuneration for the wronged party in relation to time and effort spent.

But time and energy seem not to matter for Azzouz right now, whose dedication to justice is palpable. “It’s not even about the articles,” she says, “it’s about teaching big sites like Dostor that they can’t just steal articles from smaller sites.” In the meantime, she and her team will keep producing popular content about fashion in and out of the Arab world – and insist that their fans read it only on Fustany.