Can Silicon Valley Entrepreneurs Solve Addressing Problems in the Arab World?

When Khaled Naim started building Addy.co in January, it was a side project conceived during a Startup Weekend. But after he debuted Addy at the StartX Demo Day this fall, while pursuing his MBA at Stanford, the online addressing system started to get some attention.

When Khaled Naim started building Addy.co in January, it was a side project conceived during a Startup Weekend. But after he debuted Addy at the StartX Demo Day this fall, while pursuing his MBA at Stanford, the online addressing system started to get some attention.

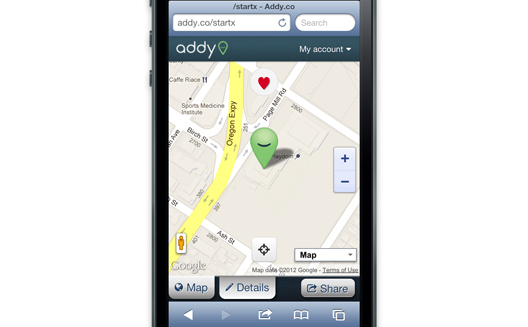

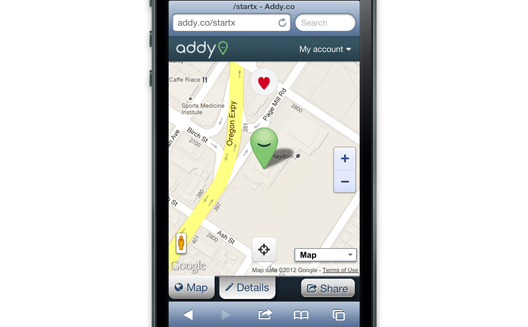

What is it? “It’s an addressing system for the digital age,” says co-founder Khaled Naim. “We still interact with today’s advanced technology using a very archaic system.” Addy, instead, is designed to allow users to drop a pin onto a map and generate a customized URL representing that location, that could be as simple as addy.co/Wamda (check it out, it’s live, and yes, we're based in Beirut).

There are existing solutions for this; I could take a Google string, zip it into bit.ly, and come up with a customized URL like http://www.bit.ly/wamda, but that string would still be a one-time offer. An Addy address is transferable to any location once you own it.

For businesses and homes in the Middle East, where standard road names and numbers are sometimes lacking, Addy.co offers convenience. Users can also add relevant notes to the location like where to park, which buzzer to press, etc.

An Addy is a bit like the Geo Reference Locator that localsearch.ae built for the UAE, giving every location a six digit number, but Addy puts the user in complete control. Addy is also similar to what enwani.com does for Saudi Arabia, offering users the ability to find their address on a map and then save it to their phone number. Yet Addy will also be for mobile, and will be more portable than an address linked to a single phone number.

“The difference between Addy and these other services is that it’s simple to communicate verbally and over text, and it’s easy to access on any device; it’s simply more user-friendly,” says Naim.

Monetizing

Part of the difficulty of pinning down (pun intended) Addy’s product is that there are many possible uses. In Silicon Valley, where its founders are building it, the immediate plan seems to be building a large userbase of casual users.

Yet in the Middle East and emerging markets that they are targeting, it might make more sense for Addy to focus on a honed enterprise solution; if it wants to make money, it will likely have to go SMS or B2B.

Simply because, from this user’s perspective, sharing your address in Beirut, Amman, or Cairo is annoying, but it’s unclear whether users will be willing to pay for the convenience of a new address service.

Wisely, Addy’s founders are already moving towards customized solutions, working on partnerships with third parties and building an API so that delivery and logistics companies can locate home addresses directly.

Working to Solve Emerging World Problems

Out in Palo Alto, the founders are working hard at iterating the product. David, one of the co-founders, left his Stanford computer science MS to lead Addy’s API development. (“He graduated from Carnegie Mellon in three years with a double major,” says Naim. “He’s the smartest guy I’ve ever met.”)

Their other co-founder, Mikel, the VP of engineering, who builds the backend, worked at IBM and then a few startups, including SocialDeck, a social network and mobile gaming company acquired by Google two years ago. Before Addy, he and Naim built Opinia, an platform designed to use natural language processing to determine crowd opinion on a given item.

Naim himself, who speaks energetically about his work, grew up for the most part in Dubai, before heading to the University of Michigan for a B.A in computer engineering. After working for two years as an IT consultant in DC, he quit and moved to the Bay Area for an MBA.

But he quickly discovered that building a company during a startup boom comes with its own challenges. “The energy in the Valley is unparalleled,” he says. “There are so many exciting startups, but this makes recruiting talent very competitive.”

As we discussed the issues over chai at the University Café on University Avenue, it’s clear that Addy has a ways to go before its founders will be certain exactly who the app’s biggest users are (and they may want to understand how companies like Aramex handle the issue of recording addresses). Yet their focus on solving a tangible in the Middle East is guiding them.

“It’s easy to narrow your focus to the U.S. when you're out here. But here are 6.5 billion people in the rest of the world, most of whom can’t even have something shipped directly to them. They don’t have access to many services we take for granted,” says Naim.

“Traction has started to pick up around here,” he admits. “But we remain convinced that the real pain lies in the developing world, and we intend to focus our efforts on product-market fit in the Middle East and other emerging markets.”